At the Hall of Fame, the first order of business for Director Angell after World War II was the election of 1945, the tenth quinquennial since founding. After the election, Dr. Angell wrote to, among other electors, Henry M. Wriston, President of Brown university, that in spite of the great interest shown by the 97 electors, four did not vote, and that had not the election rules been altered during the balloting, the shocking result of 1940 would have been repeated.

In that earlier election, only one person had been admitted — for reason that in 1922 Robert Underwood Johnson had increased the entrance requirement to a three-fifths majority, so as to keep out second-raters, and to bring admissions more in line with installation ceremonies.

Dr. Angell was “happy to report” that as a result of, in effect, changing the rules in the middle of the counting, they were able to add to the Colonnade the names of Booker T. Washington, Thomas Paine, Walter Reed and Sidney Lanier. Otherwise, only Washington would have been chosen.

The NYU Senate, having had the right to make the three-fifths rule, also had the right to change it back to a simple majority. They promptly did so. An embarrassing question was: “If you can do it for Lanier, Reed and Tom Paine, why could you not have done it when only Stephen Foster was elected in 1940?” Or is only Foster had gone in then, why could not Booker Washington go in alone now?

Straw voting is not uncommon. Official voting, followed by discussion and revoting, has seldom been considered a worthy practice in democratic elections, though it has been known to happen in more than one setting, not excluding academe. Governmental councils in the ancient Middle East were accustomed to passing judgment under cups and reviewing their decisions on sobering up the next day. At any rate, the NYU Senate took the chance and weathered the storm. Besides, who could complain at the election of such worthies as Paine, Reed and Lanier?

The New York Times could: “Why did Thoreau who is much better known than Sidney Lanier . . . get only 36 votes to Lanier’s 48?” One answer was that Lanier was sponsored by four electors. Another was the strong support of the Daughters of the Confederacy. “If the elections were by universal suffrage,” said the Times, “one might profitably generalize . . . Since the choices were actually made by an aristocracy of 100 men and women . . . all one can do is wonder . . . There are more famous men outside the Hall than in it.”

Sidney Lanier might not have been named if all the electors had voted. Four did not, and Lanier squeaked in — fame by merit, the helping hand of fate and four friendly electors. A neat “inside” job.

Angell presided over the ceremony for the bust of Booker T. Washington in May, 1946. Recurring illness prevented his doing much thereafter, and he died in March, 1949. There is not reference in the Dictionary of American Biography to his work with the Hall of Fame.

On appointing Angell, the University “had hoped that with the more time he then seemed to have at his disposal he might serve as more than simply a figurehead and assist the long neglected job of making this American Valhalla better known and more influential across the country, which entailed of course some degree of enhancement of finances. So we appointed Dr. Angell . . . and no one could have excelled his performance” — at the few public ceremonies at which he appeared.

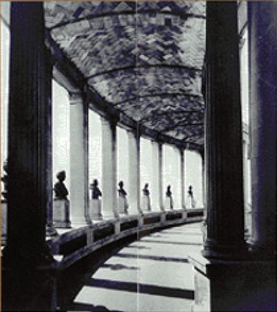

The Colonnade

Hall of Fame Brochure