Director Johnson appeared to take great pleasure in his ceremonies. Most public ceremonies — indeed all ceremonies, if they go on long enough — have as many low points as high points. Now inspirational, now absurd, they produce pleasure and tedium, indifference and nodding in varying measures.

One ceremony during Johnson’s day was a surfeit of celebration — the memorial service on 1932 on the 200th birthday of George Washington. Honors to General Lafayette added a fillip to the occasion, and the auditorium of Gould was filled with French and American plenipotentiary.

A tenor from the Metropolitan Opera sang both national anthems. Edwin Markham read a poem he composed for the event. There were three tributes to Lafayette by the Rector of the University of Paris, by the French Academy, and by a high military attache. On the American side jurist Samuel Seabury drew applause when he called Washington the greatest figure of his age. Since the statement came as no surprise, part of the clapping may have been for Seabury himself. In 1932 he was the hottest number in anti-corruption circles for having nailed in that year both Mayor James Walker and Tammany Hall. Director Johnson knew the value of current as well as enduring fame.

The audience listened with what Chancellor Brown called “peculiar pleasure” to the principal address by essayist Agnes Reppelier who, “after all the long program had unrolled was still able to produce a climax, a very cheerful and happy one.” Her description (reported in the New York Herald Tribune) of General Washington as a soldier lacking the “hat waving, sword flourishing, white plume of Navarre business: got an enthusiastic ovation. She pictured him as a “statesman lacking the hail-fellow-well-met manner which covers a lot of sins . . . Silent, reserved, distinguished and discerning,he stood by what he knew to be right, and he strove for what he believed to be attainable.”

(Thirty-one years earlier, scholarly journalist Talcott Williams, writing in the “Official Book” of the Hall of Fame, had been equally impressed with Washington’s deeds — but with some reservations. “He was deemed dull by his contemporaries. There is a tolerably well authenticated transcription that . . . the elder Adams said Washington was a stupid man who won his reputation by holding his tongue.”)

As a talented versifier, to say the least, Johnson had a way of presenting his own lines at public celebrations. He wrote verse from early manhood to old age and published seven volumes of it, ending with Poems of Fifty Years.

In 1926, Johnson improved an unveiling ceremony by reciting the work of another poet, Chancellor Elmer Ellsworth Brown. He opened with a touch of hyperbole: “Mr. Chancellor: I know of no words in the English Language more appropriate to the opening of these ceremonies than your beautiful poem Processional. You say

With kindling hearts again we tread

The pathway of the mighty dead.

Where meet and pass their spirits high

Who, tasting death, disdained to die.

We hail them, fathers of the free

And prophets of our destiny.

Who, from their starry height control

The tides that flood a Nation’s soul.

In high humility we claim

Our birthright in their hallowed fame,

With widening vision we would rise

To the horizon of their eyes.

God of our father, grant that we

Who keep their sacred memory

Fail not when prophecy again

Shall smite and rouse the souls of men.

The resemblance of the cadence to that of Kipling’s Recessional may be coincidental. Lofty occasions call for lofty measures. And though the Chancellor’s poem may not be of the Golden Treasury, we recall that the words of many a sacred hymn divorced from the music make commonplace reading. Alternately, good verse can turn popular music into a national hymn. The powerful words of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, heard to the rousing tune of John Brown’s Body, were sung with gusto at Winston Churchill’s funeral. Singing might have given Chancellor Brown’s verse the lift it deserved, that it cried for.

Dr. Johnson had the good form — always that at least, in word and conduct — not to read any of his own poetry that day. Propriety, however, did not preclude the printing of one Johnson selection in the program. While they waited, witnesses to the unveiling ceremony were able to enjoy The Hall of Fame at Night. The opening and closing stanzas give ample evidence of the quality of all:

By day the city's noise and blight

Usurp the spirit's throne;

The silence of the truthful night

Restores it to its own.

O ye that gladly paid the price

That made your names renowned

The precincts of your sacrifice

Are our most holy ground.

The fourteen quatrains that fall between the first and the last show more of the same.

Readers who were taught the great English poets of the nineteenth century –the Romantics and the Victorians — and who get tired of the vers libre without rhythm or rhyme, that was heard in the 20’s and 30’s — might try the out-of-print has-beens such as Robert Underwood Johnson. Some of his relaxed verse does not have to be construed to bring a smile of appreciation. Though we can take exception to his public pretensions, we may find a pleasant hour in some of his even measured, old-time verse of simple feeling. For example: America in France, reminiscent of Robert Browning: “O to be in Paris, now that Pershing’s there,” a joyful parody, whether intended or not.

As a platform speaker Johnson was in the mold of the great orator of Dedication Day, Senator Chauncey DePew, and his greater predecessor, Senator Edward Everett of Gettysburg “fame.” Johnson too had mastered the art of transforming fancy into classical oratory:

The dominant notes of this occasion should be patriotism, rejoicing, and hope. At this moment in this already historic place our imagination looks backward and forward — backward with grateful reverence and pride to the character and achievements of those whose names are here honored, and forward to the inspiration and influence which, in peaceful or troubled times, they will exert for good upon our people. It is not too much to say that the Colonnade of the Hall of Fame is already a bulwark of American liberty.

I bring you today, Mr. Chancellor, nine more tributes in bronze to personages whose names are in the Hall of Fame. Thus, within five years there have been dedicated thirty-six of these effigies, each a tribute from some group of patriotic citizens who have realized the value and permanence of this unsectional, unpartisan and unsectarian memorial. Each one of these bronzes is like a bell that sounds a new note in our carillon of national fame. They shall proclaim our countrymen and to all who came to us from abroad messages of opportunity and faithfulness, of sacrifice, of sympathy, of charity, of ideality . . .

Common sense, good feeling and balderdash, high sounding. Still, if the “effigies” do not sound like bells, it must be acknowledged that Johnson himself and has associates put them there out of care and hard work. One of them was Mark Twain, unveiled in 1924, in whom there dwelt a gloriously great writer and a vulgar boatman of profane tongue.

It is not too much to say that such public outbursts may help us understand why Mark Twain’s secretary, wrote in her notebook, “Sometimes he [Twain] is much irritated by people. He hates Mr. & Mrs. R.A. Johnson. He grits his teeth at the mention of either of them.”

The last sentence of Johnson’s address, before turning over the lectern to the Chancellor, has, to this day, the ring of a truth seldom heard: “These [men and women] fortify our confidence that whatever may be our national perils of defects, our faults or foibles, we have always in our soil the imperishable seeds of greatness.” He is speaking here not of our leaders in the public eye but of those in reserve, the auxiliaries who live quietly and work hard and well in anonymity and who rise to notice only when called upon. How long the supply will last is another question.

The image of a carillon remained with Johnson for years. In 1934 he proposed to erect on University Heights campus in front of the Gould Library, a tower in which, wrote Chancellor Harry Woodburn Chase, there would be:

. . . a carillon of bells, finer and noisier than [Harry Emerson] Fosdick’s [of Riverside Church]. On top of this and I suppose sufficiently substantial not to be jarred by the bells he wants a statue of Fame with wreaths [and a four-faced clock], the whole being pointed toward the Hall of Fame. He thinks he can get the statue, but I do not think he has the foundations yet in sight . . . It wouldn’t at all surprise me if one of these days he should turn up with some money . . .

The tower had been included by McKim, Mead and White in the original plan for the uptown campus and was by his own admission Johnson’s “beloved project.” He added, clever man, that “it cannot fail to carry the name of its generous donor.”

He never got his tower of bells. If he had succeeded, and if the tower had been as tall as the sketch indicated, it would have afforded the best view of the upper city.

Strengths and weaknesses together, Johnson was nothing less than the most able, indeed, the greatest Director of the Hall of Fame under New York University. Before he assumed office, 56 members had been elected and their names tabulated, but only two had been sculptured. The assignment looked impossible. During his term, therefore, only

sixteen new names were voted in — by his decision, on his reasoning: first after 1925, the time requirement for eligibility was increased to twenty-five years after death, second, for twelve of RUJ’s seventeen years in office, a three-fifths vote was required for election instead of a majority. The selection process was thereby made more judicious, less subject to predilection.

For one thing — whatever one may think of how and why it happened — during Johnson’s tenure the election of clerics came to a halt. No one classified as preacher or theologian has been elected since 1920, when Roger Williams, founder of Rhode Island, was chosen, the last of five to make it. The first three and been elected in 1900.

- Jonathan Edwards (1703-58), greatest preacher of the rigid Puritanism (Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God) that gave America courage and spirit in the face of hard physical obstacles and helped it grow strong, got an impressive 82 votes and tied Samuel F.B. Morse as our twelfth most famous man.

- William Ellery Channing (1780-18430 leader and principal force of the Unitarian movement in the early nineteenth century, preached confidence in the goodness of human nature and influenced such other early Hall of Famers as Emerson, Longfellow and Lowell with his powerful arguments, particularly the one against Calvinism, the extinction of which, in Channing’s words was a “consummation devoutly to be wished.”

- The lusty and brash Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887) also made it into the Hall on the first round, even though he had not met the waiting requirement of 25 years that had been announced at the founding. His more famous sister, Hariet, had to wait until 1910. Beecher, impressed by his own lionesque head and the sound of his own voice, started a phrenology club as a student at Amherst and went on to become the nation’s most famous preacher and platform orator — a golden, sometimes loose tongue and a one-man pressure group for whatever movement he found appealing and had calculated to be destined for success.

In the post civil war era Beecher was, perhaps unknowingly, one of the most influential opponents of hell-fire Puritanism. He made prospering America feel self-confident and stirred a sense of the joy of living. Not even the noisy scandal over adultery with a lovely parishioner could entirely alienate the Reverend Beecher from the 2,500 persons who packed the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York, every Sunday to hear his colorful sermons. Other thousands enjoyed them in print. - Phillips Brooks (1835-1893) rector of Trinity Episcopal Church of Boston, author of O Little Town of Bethlehem and the first American to preach before Queen Victoria in the Royal Chapel at Windsor, joined the first three in 1910.

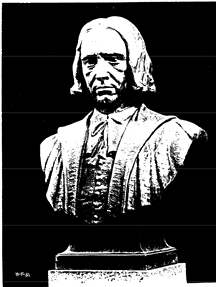

During the seventeen Johnson years, 72 new busts were set on pedestals — a prodigy of acquisitioning. Johnson also created a unity of style, and considerably improved the overall effect of the Colonnade. He frowned on the placement of replicas that seemed likely to become the custom with the acceptance of the first two busts — replicas of Mann and Fulton. He opposed the idea of “irregularity of scale” that would surely have followed Henry Mitchell MacCracken’s willingness to accept statues, busts, portraits, or even a few odds and ends in the “Museum” below. Johnson made sure that no donor of a bust could dictate the terms of its installation. He kept a critical eye on the entire complex and its decoration, reminding us that it was a sound architectural principle “to ornament a construction but not to construct an ornament.”

Robert Underwood Johnson died in office in 1937, leaving the Hall of Fame world-famous, sitting on the heights.

His greatest achievement, however, had not been his first love. That distinction was reserved for the American Academy of Arts & Letters, which he had helped found in 1904. According to biographer Louis Starr, Dr. Johnson wrote its procedures for selection of members and was its secretary for the rest of his life. He was also devoted to the Century Association, a club for “amateurs of arts and letters.” Because of his conservatism, doubt was once raised as to which century Dr. Johnson had in mind.

He is remembered by older Americans as father of famous Owen Johnson, a good novelist and author of the well known Dink Stover books, e.g. Stover at Yale.

Most of the directors after Johnson were, like him, men who were closing out illustrious careers, which they topped off by accepting what amounted to a sinecure in the Hall of Fame. Themselves possessing a measure of fame, they lent dignity and luster to maintain the reputation of the shrine. They were superb “front men”, they also had other jobs, and the Hall of Fame did not enjoy highest priority.